By Daniel Minden

Canadian federalism jurisprudence should provide the federal government with firmer ground to exercise authority over foreign affairs, Toronto lawyer H. Scott Fairley argued last week.

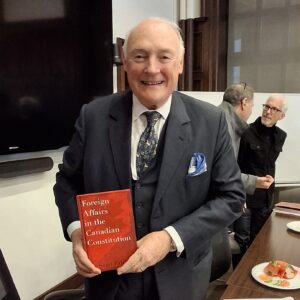

On February 5, 2026, the David Asper Centre for Constitutional Rights hosted H. Scott Fairley, with Professor David Schneiderman as discussant, for a Constitutional Roundtable at Jackman Law. Fairley, a partner at Cambridge LLP, presented themes from his recent book Foreign Affairs in the Canadian Constitution (UBC Press, 2025). Fairley argued that an overly broad provincial role in foreign affairs displays disunity and invites aggression, citing James Madison, who wrote that if his country was to be “one nation in any respect, it clearly ought to be in respect to other nations.”

Historical evolution of the foreign affairs power

Fairley began by providing an overview of the evolution of the federal foreign affairs power since 1867. Unlike the written constitutions of other federations, Fairley noted that Canada’s Constitution Act, 1867 mostly leaves the issue of foreign affairs unaddressed. This was deliberate, Fairley contended, since Canada’s foreign relations were handled by the British Empire before the First World War. Illustrating this point, s. 132 of the Constitution Act, 1867 gives the federal Parliament “all Powers necessary or proper for performing the Obligations of Canada or of any Province thereof, as Part of the British Empire, towards Foreign Countries, arising under Treaties between the Empire and such Foreign Countries.”

While s. 132 might have been fit for purpose at the time of Confederation, following the 1923 Canada-U.S. Halibut Treaty Canada began to negotiate its own international treaties. As Canada forged an independent foreign policy in the years that followed, Fairley noted that s. 132 became moribund, since the provision only protects federal authority to implement treaties negotiated by the British Empire.

As the utility of s. 132 faded, provincial governments, especially the government of Québec, began to assert themselves as international actors. In the 1960s, Québec adopted the Gérin-Lajoie doctrine and claimed a right to conduct international relations in all areas of provincial jurisdiction.

Tracing the evolution of jurisprudence

Fairley noted that constitutional jurisprudence in Canada has both protected and constrained the federal government’s ability to implement treaties.

In the Aeronautics Reference [1931] UKPC 93 (BAILII) and Radio Reference [1932] UKPC 7 (BAILII), the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council (JCPC) held that broadcasting and aeronautics fell within the federal vires, relying in part on the fact that international treaties governed the two matters. However, in the Labour Conventions Reference [1937] UKPC 6 (BAILII), the JCPC held that although the federal government could enter into treaties, the performance of those treaty obligations “depends upon the authority of the competent legislature or legislatures.” In other words, the federal government could not intrude on a provincial vires on the basis that Canada needed to fulfil its treaty obligations.

The Charter and judicial review of the royal prerogative

Fairley also pointed out the consequential role of the Charter in enabling courts to review federal Cabinet decisions involving foreign affairs issues. The foreign affairs power exercised by Canada has its basis not in the text of the Constitution Act, 1867 but in the vesting of the royal prerogative in the Canadian government. Until a few decades ago, courts regarded the exercise of the royal prerogative as non-reviewable, Fairley contended. However, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms led courts to accept the reviewability of Cabinet decisions on foreign affairs.

In the landmark case Operation Dismantle v. The Queen [1985] 1 SCR 441, the Supreme Court of Canada held that “decisions of the federal cabinet are reviewable by the courts under the Charter, and the government bears a general duty to act in accordance with the Charter’s dictates.” The Supreme Court reaffirmed this principle in Canada (Prime Minister) v. Khadr [2010] 1 SCR 44, when it held that “in the case of refusal by a government to abide by constitutional constraints, courts are empowered to make orders ensuring that the government’s foreign affairs prerogative is exercised in accordance with the constitution.”

A proposed addition to the national concern doctrine

Returning to the topic of federalism, Fairley argued that the Supreme Court of Canada should modify its test for the national concern doctrine so that the federal government can more easily claim jurisdiction over foreign affairs matters.

As the Supreme Court of Canada held most recently in Reference re Greenhouse Gas Pollution Pricing Act (“Greenhouse Gas”), for a matter to be a matter of national concern, over which the federal government can claim jurisdiction under its Peace, Order, and Good Government (POGG) power, the matter must satisfy a three-part test. The matter must (a) be of sufficient concern to Canada as a whole, (b) have a singleness, distinctiveness, and indivisibility that clearly distinguishes it from matters of provincial concern (c) have a scale of impact on provincial jurisdiction that is reconcilable with the fundamental distribution of legislative power under the constitution.

In Greenhouse Gas the Court also held that part (b) of the test may include a consideration of “the effect on extra‑provincial interests of a provincial failure to deal effectively with the control or regulation of the intra‑provincial aspects of the matter.” This seems to have led Fairley to adopt a proposed addition to the test, which could cut in favour of many foreign affairs issues being intra vires the federal government.

In his lecture, Fairley proposed that the Supreme Court should add to the test that “national incapacity to address a matter of international concern independent of collective action [through a treaty]” should also be relevant to the determination of distinctiveness and indivisibility under the national concern doctrine. This would enable Canada to argue that global challenges such as pandemics and climate change, which require collective action, are within federal jurisdiction.

Driving a truck through federal-provincial equilibrium?

Professor David Schneiderman asked Fairley to consider whether this proposed addition to the national concern doctrine test might weigh too heavily in favour of federal power, threatening the constitutional equilibrium between the provinces and the federal government. Fairley responded that his proposal is consistent with equilibrium in its modern form, noting that Canadian federalism jurisprudence has long abandoned the notion of federal or provincial watertight compartments.

Fairley argued that any notion that each order of government can act within sterile autonomous spheres divorced from Canada’s obligations abroad is no longer realistic. Rather, there now exists an extensive overlap between the provincial vires and federal vires as the doctrine of cooperative federalism appreciates. For Fairley, despite the importance of federal-provincial cooperation, Canadian courts must appreciate the distinctiveness of matters requiring collective action, where Canada depends on other nations and other nations depend on Canada.

Fairley wrapped up his talk with a classical allusion by evoking the memory of Themistocles, who helped to unify Athens with its neighbour Piraeus. That unity was essential in enabling Athens to defeat an invasion by a more powerful Persian force.

Daniel Minden is a Research and Communications Assistant with the Asper Centre. He is a 1L JD candidate at the University of Toronto Jackman Faculty of Law.