The Asper Centre Constitutional Roundtables are an annual series of lunchtime discussion forums that provide an opportunity to consider developments in Canadian constitutional theory and practice. The series promotes scholarship and aims to make a meaningful contribution to intellectual discourse about Canadian and comparative constitutional law.

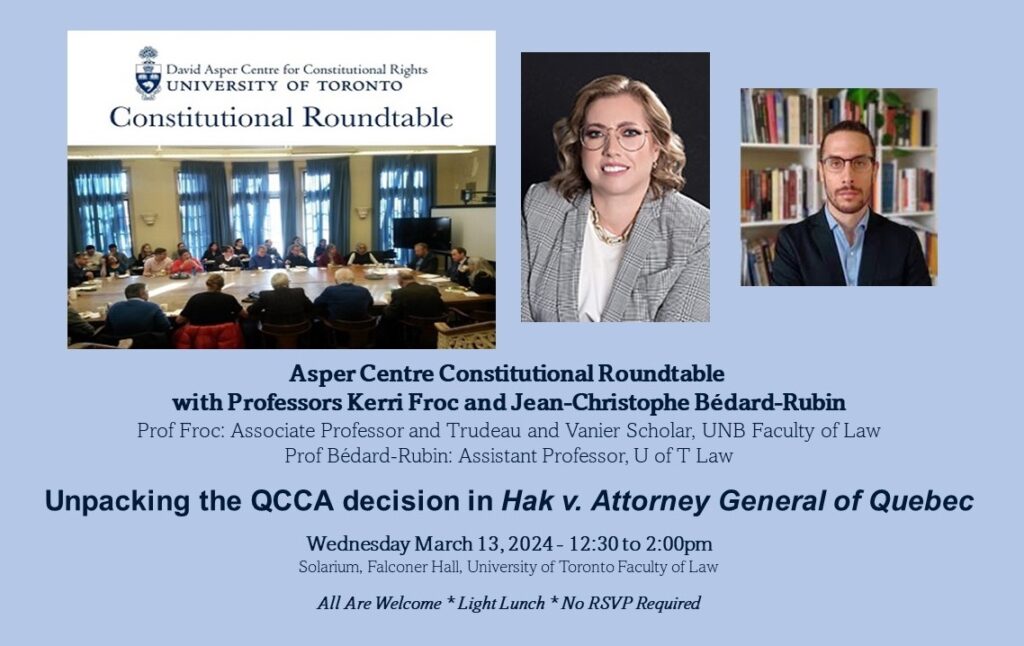

We are pleased to host Associate Professor Kerri Froc (UNB Law) in conjunction with Assistant Professor Jean-Christophe Bédard-Rubin (U of T Law) for a Constitutional Roundtable on March 13, 2024 in the Solarium, Falconer Hall, Faculty of Law.

Professors Froc and Bédard-Rubin will break down the Quebec Court of Appeal’s decision in Hak et al. c. Procureur général du Québec, concerning the constitutionality of Bill 21, An Act Respecting the Laicity of the State. This appeal concerns freedom of expression, freedom of religion and equality rights, as Muslim women in Quebec who wear religious symbols such as the niqab or hijab would be prohibited from working in certain professions and in most parts of public administration, and prevented from benefitting from some public services because the law requires them to do so with their faces uncovered. The government of Quebec also pre-emptively used the override clause to prevent any constitutional challenges to the legislation. This Constitutional Roundtable will cover what this decision means for Charter rights, gender equality, and state use of the “notwithstanding clause.”

Kerri Froc is an Associate Professor at UNB Law, as well as a Trudeau and Vanier Scholar. She has taught courses at Carleton University, Queen’s University and University of Ottawa on feminist legal theory and various aspects of public law, among others.

Kerri received her PhD from Queen’s University in 2016 and holds a Master of Laws from the University of Ottawa, a Bachelor of Laws from Osgoode Hall Law School and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Regina.

Before completing her doctorate, she spent 18 years as a lawyer, as a civil litigator in Regina, a staff lawyer for the Women’s Legal Education and Action Fund (LEAF), and as a staff lawyer in the areas of law reform and equality at the Canadian Bar Association. She is a member of the Saskatchewan and New Brunswick bars.

Assistant Professor Jean-Christophe Bédard-Rubin’s work explores Canadian constitutional culture from historical and comparative perspectives. He studied law, political science, and philosophy at Université Laval, Yale University, and the University of Toronto. During his doctoral studies, Jean-Christophe was the McMurty Fellow of the Osgoode Society for Canadian Legal History and a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Scholar. He has done consultancy work on constitution-building for International IDEA and, prior to his graduate studies, he worked in litigation for the Quebec Department of Justice.

Bédard-Rubin currently pursues two main research projects. The first is an intellectual history of the foundations of public law in French Canada. This project seeks to reconstruct the intellectual networks in which French Canadian public lawyers participated to excavate the transatlantic influences on the formation of Quebec’s legal syncretism. This genealogical reconstruction recovers the conceptual and theoretical innovations that allowed French Canadians to articulate a genuine theory of the state outside of the revolutionary framework. In so doing, this work sheds a different, somewhat oblique light on Canada’s constitutional experience and questions its status in comparative constitutional scholarship.

The second research project investigates judicial bilingualism in Canada. Using mixed social science methods, this project explores the various empirical impacts of bilingualism on judicial behaviour, the normative significance of legal bilingualism for the authority of judicial decisions, and the ways in which language shapes the dominant conception of the judicial role in Canada’s French and English public spheres.

Jean-Christophe’s work has been published in English and French in the Review of Constitutional Studies, the Canadian Journal of Law & Society, the Osgoode Hall Law Journal, the Bulletin d’histoire politique, and the International Journal of Canadian Studies, amongst others.

All are welcome * Light lunch provided * No registration required